HOME PROFILE RESEARCH CODES PHOTOS CONTACT

Stars, Clouds, and Feedback

My research revolves around three things: the gaseous environments where stars are born, the stars, and the energy released as they evolve. This energy, known as stellar feedback, in turn shapes the stars’ birthplace.

Star formation is a multi-scale problem. Things going on from the galactic scales down to the scales of accretion discs are inter-connected. I’m interested in the intermediate scales - the Giant Molecular Clouds. They lie along the galactic spiral arms. Turbulent cloud gas collapses under self-gravity to become dense sheets and filaments. Then, when the clumps become sufficiently cold, stars and clusters may begin to form.

The initial stellar masses generally obey a lognormal distribution, but with a distinct power-law tail. This tail indicates the rare presence of Massive Stars. Despite their small numbers, their feedback dominates the energy budget in our Galaxy. Ionizing radiation, stellar winds and Type II supernovae are all examples of it. Without feedback, stars would form extremely quickly and die out within a very short time.

But how much of those feedback energy actually went into sustaining the star-forming regions? How do we get the massive stars? Does feedback help or hinder their formation? These are the kinds of questions to be solved.

I worked on a few different projects. Scroll down to see more!

Massive binary accretion in clusters

We zoom in a little onto the cores of individual clusters. This is a new project initiated by Ian Bonnell and Jesus (Miguel). The competitive accretion theory (e.g. Zinnecker 1982, Bonnell et al. 2001) tells us that massive stars tend to form at the central regions of stellar clusters. This is because a cluster’s overall gravitational potential can funnel materials towards its centre, allowing the protostars that happened to be sitting there gain advantages in gathering the infalling materials.

However, whether or not the incoming materials can successfully stick onto the star depends on their relative motions. For instance, their angular momenta need to be sufficiently similar. If the central massive star is stationary, that sets a limit to how much mass it can attain. Now, what if the central star is a massive binary pair with internal angular momentum, and is capable of travelling around in the cluster via N-body dynamics. Will it become even more massive? This is what we’re trying to answer.

Feedback in Giant Molecular Clouds

Massive stars inject vast amounts of energy and momentum into their surroundings throughout their lifetime. The energy often takes the form of high-energy radiation, that ionizes the nearby H2 molecules and heats them to approximately 10000 K. Meanwhile, stellar winds launched by the radiation pressure can sweep materials into thin dense shells, sculpting voided bubbles in the GMCs.

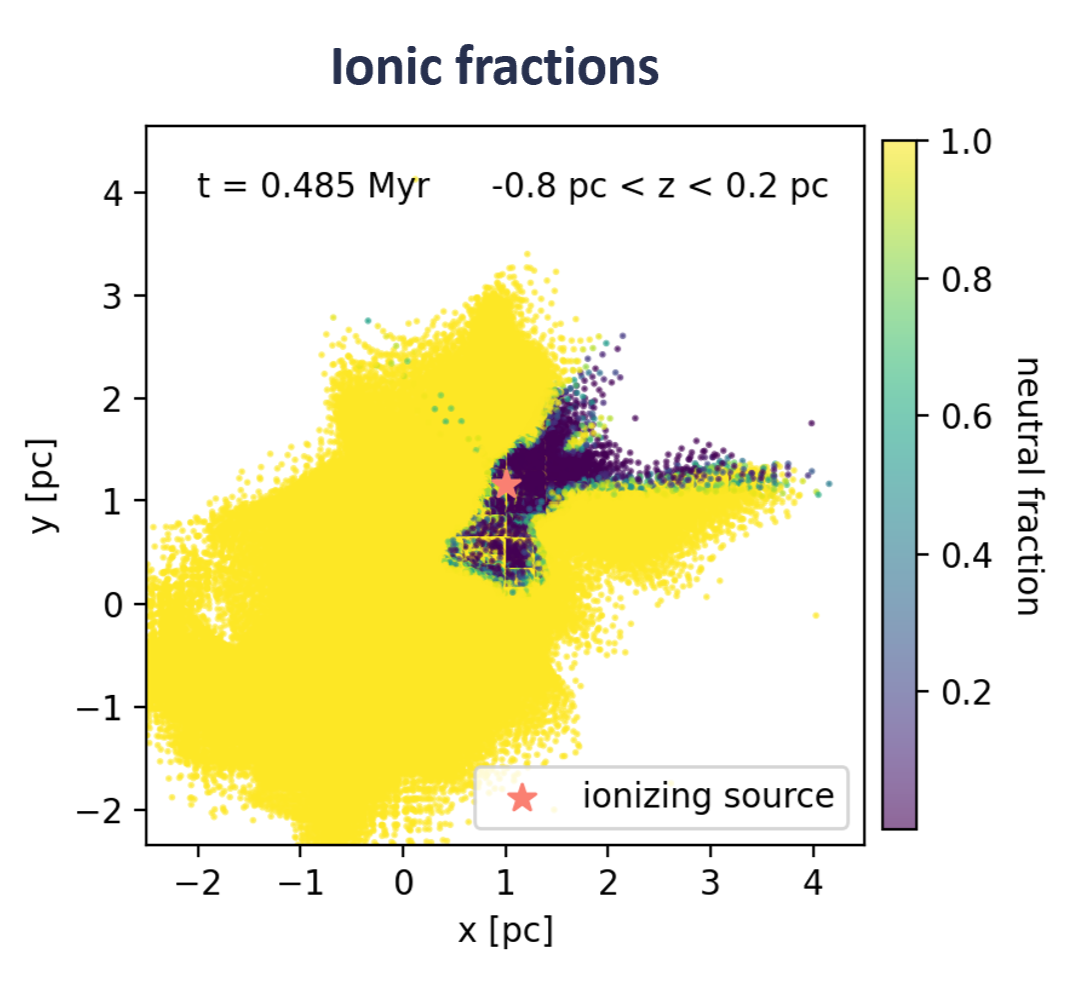

It might sound destructive. But in reality, a notable aspect in the behaviour of feedback is that they tend to pass through the paths of least resistance as they escape their natal GMC. This is much like rivers passing through pre-existing valleys and eventually carving the gorges. If we take a slice from the cloud and plot the location of particles impacted by photoionization (i.e. ionized; coloured in purple), we see that their morphologies clearly exhbit cavity- and channel-like structures.

Thus, when the progenitor star dies, if the GMC gas is yet to be dispersed (being too big or is enveloped by warm HI gas), its supernova explosion could be “trapped” in these cavities. Their energies are then swiftly “channelled” out of the GMC, thanks to the early feedback, without significantly impacting the dense star-forming filaments.

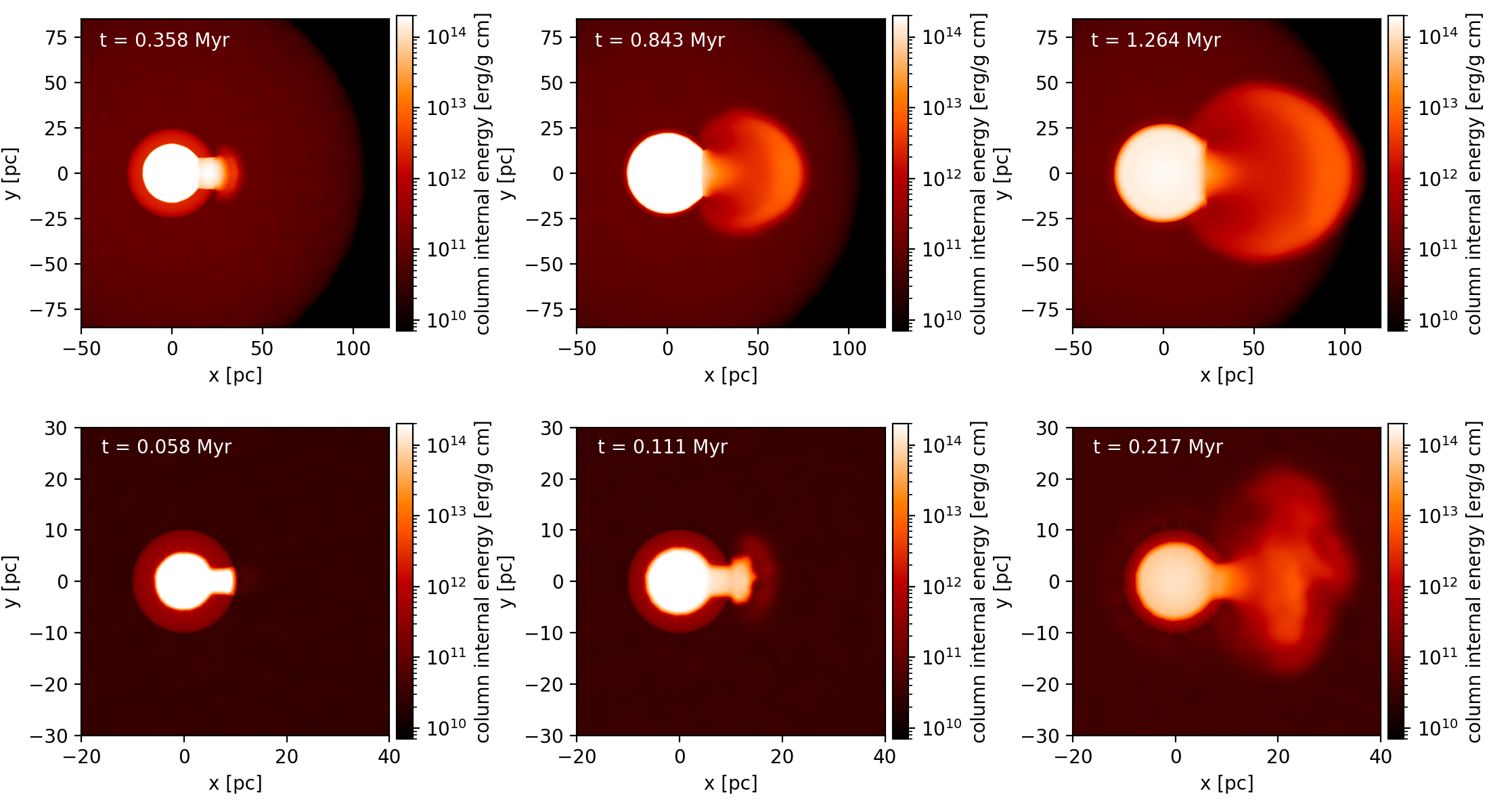

Let’s look at the example simulation below. If we try injecting supernova into a GMC where early photoionization feedback is present, we see that the explosion energy is escaping like blobs running away in bipolar directions. The explosion is not spherically symmetrical. There are even slight time delays between the shocks!

We probably need a new model to describe this partial confinement behaviour in the supernova energy release. Why? Because it’s particularly important for galaxy simulations, where sub-grid feedback recipes are crucial.

A semi-confined Supernova explosion

If you think about it, this scenario now becomes fairly analogous to a “semi-confined explosion”, a modelling problem that has been well-studied in engineering for decades to understand bomb impact inside buildings. (You might hate engineers but please just read on.) What we could do is to simplify the geometry of this astrophysical problem, and try put the supernovae into spherical clouds with well-defined channel openings. I called this a “semi-confined supernova” model. It allows for a robust study of the impact of confinement by early-feedback-carved bubbles.

With both analytical and numerical approaches, I showed that a semi-confined supernova, compared to a standard symmetrical one, is more capable of sustaining its local dynamical perturbation. It keeps more of its kinetic energy and momentum locally, and can induce a higher level of solenoidal turbulence, which is good for regulating star formation. We therefore argue that the semi-confinement effects are highly important in feedback modelling, and we need a way to somehow incorporate it in our sub-grid models!

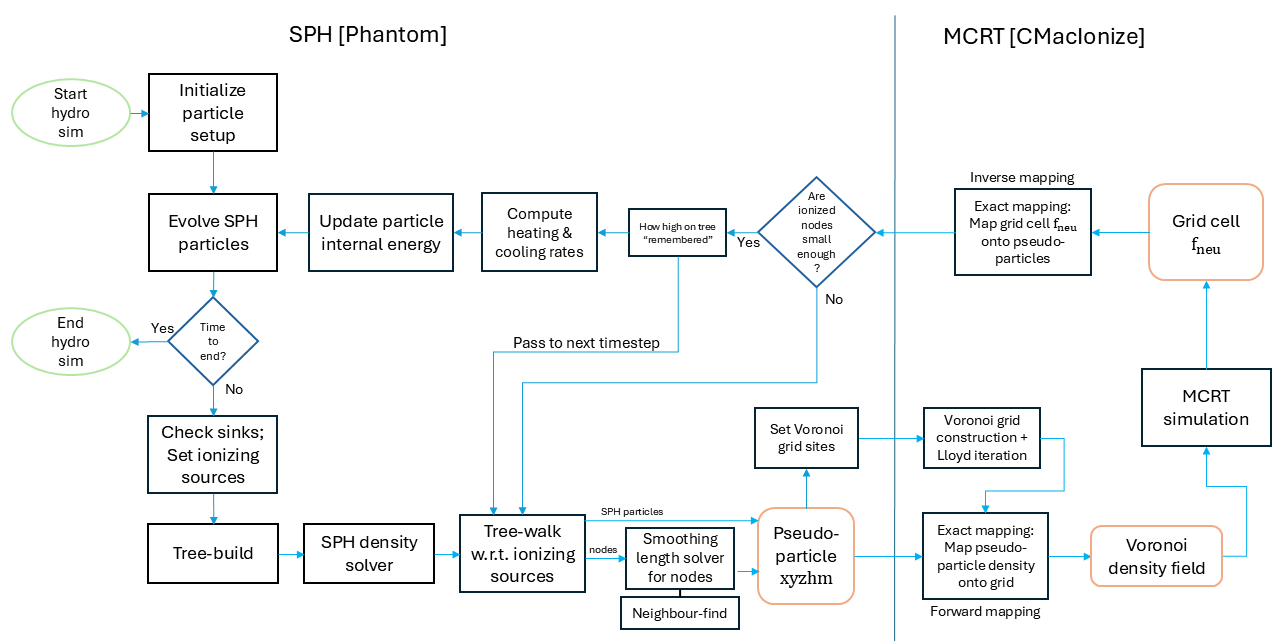

Tree-based SPH-MCRT coupled Radiation Hydrodynamics

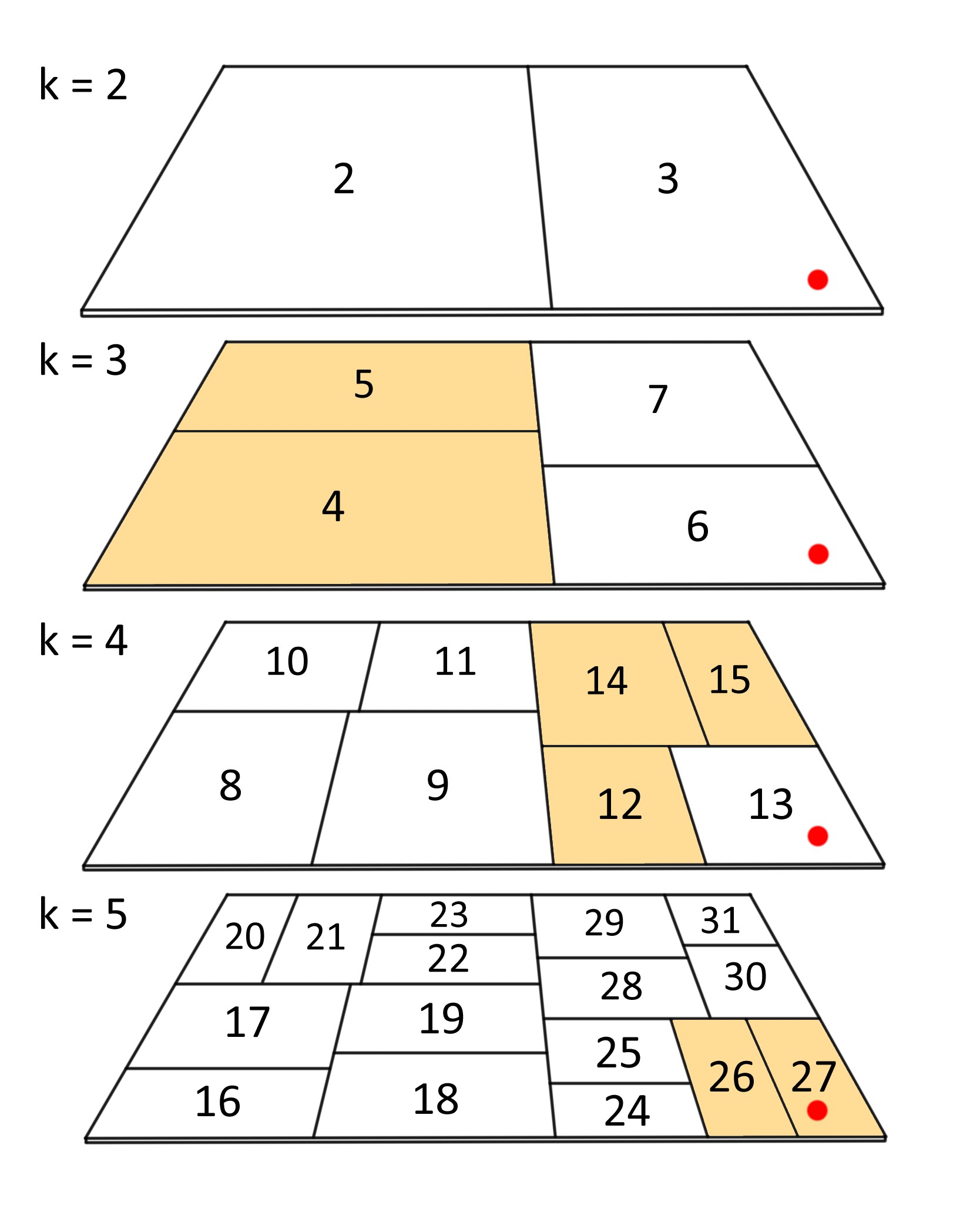

Simulation code building is another favourite activity of mine. This project was a continuation of Maya’s PhD work, where she developed a radiation hydrodynamics (RHD) scheme by coupling Phantom SPH to a grid-based Monte Carlo radiative transfer (MCRT) code CMacIonize (CMI) for modelling photoionization. It works by passing particle densities from SPH to the MCRT code at each timestep, and running an MCRT simulation on this gridded density field. Once that’s completed, the steady-state ionic fraction of each cell is computed. This information is then returned back to the SPH code for heating the ionized particles, and the simulation continues.

This RHD scheme involves transferring fluid densities between SPH particles and Voronoi cells. Maya developed the insane Exact mapping method, with which the SPH kernels can be mathematically integrated over the volume of any Voronoi cell. This is an extremely accurate way of mapping interpolated densities between Lagrangian and Eulerian descriptions, though expensive. We need a way to speed it up a little.

One way to do this is by optimizing the number of particles passed between Phantom and CMI. We only need the ionized regions to be at high resolution, whereas the neutral parts are unimportant as far as mapping is concerned. Like TreeCol or TreeRay, we decided to use the gravity tree. Ionized regions near the stellar sources shall be on particle-level. For the rest, we turn tree nodes into pseudo-particles using adaptive tree-walks, and pass them to CMI instead. Think of it as temporarily lowering the fluid resolutions, just like AMR.

Photoionization heating and implicit radiative cooling have also been implemented. The whole RHD computation now consists of 5 physics modules, and is maintained in my own Phantom fork. The self-invented algorithms are documented in this paper; they are generalisable to other SPH codes. With a tree, we can achieve up to 100 times speed up.